Cog RAM is a block of 512 longs (32-bits) of read/write memory inside the cog itself; it is used to hold Propeller Assembly programs and related data for exclusive use by that cog.

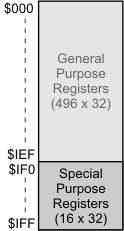

Cog RAM is divided into two sections: general purpose registers and special purpose registers. Each location within Cog RAM is long-addressable only and is usually referred to as a "register."

General purpose registers make up the first 496 longs (32-bits each) of Cog RAM. To execute Propeller Assembly code, the general purpose registers are first loaded with code and data from main memory, then execution starts at register 0. When executing Spin code, this portion of Cog RAM is first loaded with a copy of the Spin Interpreter.

Special purpose registers live in the last 16 longs of Cog RAM. The first four of them are read-only and return the values of the boot parameter, system counter, and input states for the I/O pins. The remaining 12 registers facilitate output state, pin direction, and interaction with the cog's counter modules, and video generator hardware.